This is mainly Books 1-3 of The Economy of the Covenants Between God and Man (Reformation Heritage reprint)

Book 1

Chapter 1: Covenants in General

Generally, covenants signify a mutual agreement between parties, with respect to something (43). A covenant of God, furthermore, “is an agreement between God and man, about the way of obtaining consummate happiness,” including sanctions (45). This covenant comprises three things: a) Promise; b) condition; c) sanction.

While it is a free agreement between God and man, man really couldn’t say no. Not to desire God’s promises is to refuse the goodness of God, which is sin.

Covenant of Works: in the covenant of works there is no mediator (49).

Chapter 2: Of the contracting parties of the covenant of works

The CoW = natural law = covenant of nature (50). Witsius notes that there was supernatural revelation in this covenant (53).

Image of God

The imago dei has knowledge, righteousness, and holiness (54).

Chapter 3: Of the Law, or Condition, of the Covenant of Works

The law of nature: the rule of good and evil inscribed on man’s conscience. Further, it is identical with the substance of the decalogue (62).

Witsius views the CoW as probationary, yet Adam wouldn’t have “earned” the reward per any intrinsic merit. The reward is rooted in God’s covenant, not in man’s merit.

Chapter 4: Of the Promises of the Covenant of Works

Man’s natural conscience teaches him that God desires not to be served in vain (71).

Chapter 5: Of the Penal Sanction

Nature of the soul: a spiritual substance endowed with understanding and will (89). Witsius notes that the soul is conscious of itself, which modern philosophers like JP Moreland call “self-presenting.”

Aquinas and the majesty of God: Adam’s disobedience, no matter how small, is divine treason–it is not honoring and infinite majesty as it deserves. God’s holiness is such that he cannot admit a sinner to communion without satisfaction first made to his justice (94).

Chapter 7: Of the First Sabbath

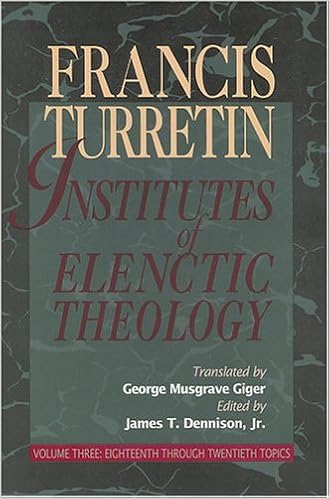

Contra Turretin, Witsius doesn’t think Adam fell on the first day (126).

Chapter 8: Of the Violation of the Covenant of Works on the Part of Man

Witsius suggests that Satan’s suggestion to Eve that she can disobey God and not die, which is a venial sin, is functionally equivalent to Rome’s definition of venial sin (138).

Foreknowledge and Predestination: God’s knowledge of future things cannot be conceived apart from his decreeing them (141). The creature acts in concurrence with God’s action. All things come from God. There is only one first cause (I.8.15). If something could act besides having God as its cause, then there would be multiple first Causes, which is polytheism.

God and sin. If all beings come from God, and even though sin is privation of being, it, too, is a kind of entity, then it also arises from God’s plan (para 22).

Chapter 9: Of the Abrogation of the Covenant of Works

The covenant of law demands a merit of perfect obedience, otherwise Christ would have been under no necessity to submit to this covenant (158).

Book II.

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Covenant of Grace

Definition: a compact or agreement between God and the elect sinner, God on his part declaring his free good-will concerning eternal salvation, and every thing relative thereto, freely to be given to those in covenant, by, and for the mediator Christ; and man on his part consenting to that goodwill by a sincere faith (2.1.5).

Chapter 2: Of the Covenant between God the Father and Son

The covenant of redemption is between God and the Mediator. The will of the Father, giving the Son to be the Head and Redeemer of the elect; and the will of the Son, presenting himself as a Sponsor or Surety for them (2.2.2). Christ’s suretyship consists in his willingness to undertake to perform that condition (2.2.4).

The exegetical foundation is in Zech. 6.13. There is a counsel of Peace between God and the Branch.

Covenant and Justification: God the Father, through Christ’s use of the sacraments, sealed the federal promise concerning justification (para 11). Christ’s baptism illustrates the sealing of the covenant from both sides.

Chapter 3: The nature of the covenant between the Father and the Son more fully explained

Lines of argument: Christ was foreordained (1 Peter i.20).

Rejects the idea of liberty of will = indifference (p. 187).

The reward the Son was to obtain:

- Highest degree of glory (John 17.1).

- Christ’s obedience is the cause of the rewards.

Chapter 4: Of the Person of the Surety

4 things necessary for a surety: true man; holy man; true God; unity of person.

Chapter 7: Of the Efficacy of Christ’s Satisfaction

The proximate effect of redemption and payment of ransom is setting the captives free, and not a bare possibility of liberty (235).

Chapter 9: Of the Persons for whom Christ engaged and satisfied

Key point: those “all for whom” (2 Cor. 5.15) Christ died are those who are also dead to the old man (257).

Chapter 10: After What manner Christ used the sacraments

Key point: Christ used the sacraments of the old covenant to show them as signs and seals of the covenant, whereby mutual contracting parties are sealed (273). The promsies made to Christ as mediator were principally sealed to him by the sacraments.

BOOK III

Chapter 1: Of the Covenant of God with the Elect

The contracting parties are God and the elect (281). The son is not only mediator but testator, who ratified the covenant with his death. Are there conditions in the covenant of Grace? Earlier divines like Rutherford spoke a qualified “yes,” though Witsius removes himself from that language. Condition: that action which gives a man a right to the reward (284).

Chapter 12: Sanctification

Witsius gives a warm and pastoral chapter on mortifying the flesh.

Concerning body, soul, spirit:

- Spirit is the mind, or the leading faculty of man (II.17).

- Soul denotes the inferior faculties.

- Yet spirit and soul aren’t two different substances.

God is the author and the efficient cause of sanctification (18).

Chapter 13: Of Conservation, or the manner by which God preserves us

God conserves us internally by the Spirit and externally by the means he hath appointed (55). This is otherwise known as “P” in the unfortunately-named “TULIP.” Our security is guaranteed because of God’s covenant, not only with us, but between the members of the Trinity (62ff).

Chapter 14: Of Glorification

Df. = that act of God whereby he translates his chosen and redeemed people to the next life.

Nature of the Soul

The soul must continue after death because the righteous who die in the Lord are considered “blessed,” yet how can someone be blessed without knowledge or feeling?

Paradise and the thief on the cross:

It makes no sense to say that the “today, I say to you” refers to when Christ spoke. The thief already knows that Christ is speaking on that day (p. 95). The thief was asking a “when” question, and Christ gives him a “when” answer.