Geisler, Norman. Systematic Theology: Introduction, Bible. Bethany House.

This book would be perfect if it were divided into two separate books. The first half would be a book on prolegomena, foundations, and apologetic method. Had I read such a book before I went to seminary, I would have been spared 8 years of wrong thinking (most of which would have been my fault). The second half is a survey of issues relating to inerrancy, bible survey and introduction, and the like.

There is quite a bit of repetition in this book. Numerous quotes by Albright, J. A. T. Robinson, and others appear over and over. Moreover, much of this book can be found in The Big Book of Apologetics/Baker Encyclopedia of Apologetics. It’s still good material, though.

Preconditions of theology:

- Mind capable of sending a message (encoder)

- Mind capable of receiving message (decoder)

- There is a common mode of communication shared by both persons.

God: The Metaphysical Precondition

Geisler defines metaphysics as the study of being.

Theism posits an Infinite, Personal God that exists both beyond and in the universe. After surveying various forms of dualism and monism, Geisler posits a form of Thomism, noting that all finite beings are composed of act and potency in their very being. Potentiality limits a finite being’s actuality, as opposed to God, who is Pure Act.

In a move somewhat rare among systematic theologies, Geisler actually defines being. It is that which is, either a mix of potency and act or a pure actuality. God is, other beings have. From here Geisler moves to his arguments for the existence of this Pure Act.

Cosmological

Horizontal argument.

(1) Everything that had a beginning had a cause.

(2) The universe had a beginning.

(3) Therefore, the universe had a Cause.

The second premise needs defending, which those from Bonaventure to William Lane Craig have done:

1) An infinite number of moments cannot be traversed.

(2) If there were an infinite number of moments before today, then today would never have come, since an infinite number of moments cannot be traversed.

3) But today has come.

(4) Hence, there were only a finite number of moments before today (i.e., a beginning of time). And everything with a beginning had a Beginner. Therefore, the temporal world had a Beginner (Cause).

Vertical Form of the argument:

This argument begins with “present contingent existence.” It argues from effect to Necessary Cause.

(1) If everything were contingent, then it would be possible that nothing existed.

(2) But something does exist (e.g., I do), and its existence is undeniable, for I have to exist in order to be able to affirm that I do not exist.

(3) Thus, if some contingent being now exists, a Necessary Being must now exist, otherwise there would be no ground for the existence of this contingent being.

But granting the arguments, would this even prove the Christian God? It will get closer than you think. Such a God would not be the one of finite godism, “since the cause of all finite things cannot be finite.” Nor can it be the god of polytheism, since there can’t be more than one unlimited being.

Miracles: The Supernatural Precondition

The problem of definition:

Weak sense: something that is not contrary to nature, only our knowledge of nature (Augustine). On this view an event doesn’t even have to be supernatural to be a miracle. This is obviously inadequate.

Strong sense: an event beyond nature’s power to produce (Aquinas, SCG 3).

A miracle doesn’t have to violate natural law. It is simply a new effect produced by a supernatural cause.

Answering objections

Spinoza: standard objection of “violating immutable natural laws.” Response: He begs the question on immutable laws. He also operates in a closed system.

Hume: Miracles are in-credible. Uniform experience is against miracles. Response: He begs the question in advance by claiming to know uniform experience. He can’t know all possible sense experiences. Moreover, as Geisler notes, “he never weighs the evidence on miracles. He simply adds evidence against them.” Even worse, Hume’s method of “adding evidence” eliminates any unique experience in history, even natural ones.

Revelation: The Revelational Precondition

The possibility of divine revelation depends on the reality of God. If God exists, which he does, then divine revelation is not only possible, but actual. The only real challenges today concern whether humans are capable of receiving this revelation (postmodernism) and whether the medium is reliable.

Geisler correctly notes that “In order for an infinite Mind to communicate with finite minds, certain things must be possible. To begin, there must be a common principle of reason that both possess.” Language and being are analogical.

Geisler’s charts are really good.

While some like to say that man’s thought sinfully distorts general revelation, and at one level that is true, general revelation is still essential to human thought. And while it is true that “Scripture determines what we believe on general revelation,” we still use general revelation (e.g., laws of logic) to make that statement.

That doesn’t fully answer the existential question: when our understanding of general revelation and our understanding of special revelation clash, who wins? Geisler says the interpretation with more certainty. Sometimes this is general revelation, sometimes special.

Logic: The Rational Precondition

Geisler summarizes here his other writings on logic. At their most basic they are:

1) Law of non-contradiction

2) Law of identity

3) Law of excluded middle.

In order to help us think better, Geisler has given a nice summary of categorical propositions:These should be written on the inside of all study bibles.

(1) There must be only three terms.

(2) The middle term must be distributed at least once.

(3)Terms Distributed in the conclusion must be distributed in the premises.

(4) The conclusion always follows the weaker premises(i.e., negative and particular ones).

(5) No conclusion follows from two negative premises.

(6) No conclusion follows from two particular premises.

(7) No negative conclusion follows from two affirmative premises.

Most evangelicals will go with him this far, but what is the relationship between Logic and God? According to Geisler, Logic is subject to God ontologically. “God is prior to logic in the order of being.” Nevertheless, God is rational by his very nature. On the other hand, logic is prior to God epistemologically. As Geisler notes, the statement “God is God’ makes no sense unless the law of identity holds (A is A).” The statement “God exists” isn’t true unless the law of noncontradiction is true.

Meaning: The Semantical Precondition

Thesis: all true statements must be meaningful. Geisler identifies three different types of schools: conventionalism (Wittgenstein), essentialism (Plato), and realism. Conventionalism is self-falsifying, for when it says all linguistic meaning is conventional, it, too, is relative.

Truth: The Epistemological Precondition

Thesis: Truth is that which corresponds to its object.

Exclusivism: The Oppositional Precondition

Thesis: Christianity’s truth claims entails that other religious oppositions are wrong (or at least cannot be correct at the same time as Christianity’s). Much of this is standard fare in evangelical apologetics, but Geisler hones in one of John Hick’s questionable presuppositions. Hick says an undifferentiated Real is known in all faiths. The problem is that an undifferentiated Real doesn’t have any definable characteristics, which means it can’t be identified. It can’t be known in any faith! Even worse, if it is undifferentiated, then no symbol can represent it.

Language: The Linguistic Precondition

Thesis: How do our concepts relate to God? They can’t be equivocal, for that would be self-defeating. They can’t be univocal, since God is infinite. Analogy makes the most sense. It allows for both similarity and differentiation. Similar to Parmenides’ dilemma, Geisler notes: “Either one’s principle of differentiation is inside of being or it is outside of being. If outside, then things do not differ in being; they are identical in being, and monism is true. The only way to maintain a pluralism essential to theism is to insist that things differ in their very being. Yet how can they differ by what they have in common? The answer is that they cannot, if being is univocal. But it isn’t.”

We’re not done yet, though. We can say that we have univocal concepts but analogical predication. The definition is the same between God and creatures, but the application is different.

Interpretation: The Hermeneutical Precondition

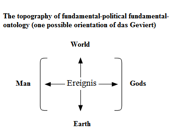

Contra Heidegger, Geisler asks how he can say Being is unintelligible. How could he know this about Being unless he understood it? Moreover, Heidegger’s denial of correspondence assumes that his denial corresponds to the way things are.

Heidegger correctly notes that man is a contingent being, yet he draws back from affirming the logical conclusion: there is a Necessary Being.

Contra Derrida, his statement that all meaning is limited by language tries to get outside those limits in order to establish them. (The rest of the criticisms flow from this critique).

Savage Burn: “it is fruitless to turn to poetry to avoid metaphysics. Metaphysical questions still exist, and they cannot be answered in anything but metaphysical language. Any so-called poetical protest is nothing more than an exercise in ventilating one’s tonsils.”

The Alternative

Can we know things objectively? Yes. The metaphysical precondition, God, has made it possible. Geisler: “The objective basis for meaning is found in the mind of God.” Much of this chapter is standard fare in grammatical-historical hermeneutics. The following is a long quote, for which I indulge the reader’s forgiveness, but it is worth noting:

Applying the six causes to meaning will help explain the point. Following Aristotle, scholastic philosophers distinguished six different causes:

(1) efficient cause—that by which something comes to be;

(2) final cause—that for which something comes to be;

(3) formal cause—that of which something comes to be;

(4) material cause—that out of which something comes to be;

(5) exemplar cause—that after which something comes to be;

(6) instrumental cause—that through which something comes to be.

Remember the example of the chair? A wooden chair has a carpenter as its efficient cause, to provide something to sit on as its final cause, its structure as a chair as its formal cause, wood as its material cause, the blueprint as its exemplar cause, and the carpenter’s tools as its instrumental cause. As we have seen, applying these six causes to meaning yields the following analysis:

(1) The writer is the efficient cause of the meaning of a text.

(2) The writer’s purpose is the final cause of its meaning.

(3) The writing is the formal cause of its meaning.

(4) The words are the material cause of its meaning.

(5) The writer’s ideas are the exemplar cause of its meaning.

(6) The laws of thought are the instrumental cause of its meaning.

In conclusion, we use the laws of logic in biblical hermeneutics. Anything else makes rational meaning impossible.

Historiography: The Historical Precondition

Method: The Methodological Precondition

The Evangelical method begins with an inductive basis in Scripture, which involves an abductive step. It will also deduce truths from Scripture and make use of analogies. He puts them all together into what he calls a Retroductive Method, worth quoting in full:

1. The Inductive Basis:

(a) God cannot err.

(b) The Bible is God’s Word.

2. The Deductive Conclusion:

(c) The Bible cannot err.

3. The Use of Analogies:

(d) Just as Christ was divine and human yet without sin, even so the Bible is divine and human yet without error.

(e) Just as nature (God’s general revelation) presents difficulties with possessing errors, so does the Bible (God’s special revelation).

4. The Use of General Revelation:

(f) The earth is not square.

(g) The sun does not move around the earth.

5. The Retroductive Method:

(h) The biblical teaching is fleshed out in view of facts known from general revelation and the data (phenomena) of Scripture.

(i) There are errors in the manuscript copies.

(j) The Bible uses figures of speech and other literary devices, round numbers, everyday (nontechnical) language, paraphrases, etc.

(k) The deductive conclusion (point c) is understood in the light of the retroductive enhancement. For example: (1) The Bible is without error only in the original text, not in all the copies. (2) Round numbers, observational language, figures of speech, and paraphrased citations are not errors.

The rest of the book is a summary and defense of inerrancy, inspiration, and the like. Some things to note, like Geisler’s chart between accommodation to error and adaption to finitude.

Note: To the everlasting embarrassment of Bible critics, at least those who claim to be followers of Christ, Jesus affirmed exactly the opposite of what much of negative “higher criticism” teaches.