Caspar Olevianus, An Exposition of the Apostles’ Creed, trans. Lyle Bierma. Volume 2: Classic Reformed Theology, ed. R. Scott Clark. Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2009. Kindle edition.

Because this book is an exposition of the Apostles’ Creed, it serves as an excellent introduction to the Christian faith. Because this exposition is by Caspar Olevianus, it serves as an excellent introduction to Reformed theology. This is an excellent introduction to the Reformed faith because its focus is not on predestination, as some commonly suppose Reformed to mean, but on Christ and the substance of his covenant, to mention one work on Olevianus (Clark, Caspar Olevian and the Substance of the Covenant, RHB). It is succinct and to the point. It is organized around the Apostles’ Creed, glossing each clause in the Creed. Some divisions are simply scripture references.

Dr R. Scott Clark’s introduction deserves its own review, so I direct the reader to my review of his above-mentioned work on Olevianus. Some points are in order, however. According to Clark, for Olevianus the gospel, the substance of the covenant, was Christ and his benefits. “Considered objectively, the substance of the covenant is comprised of God’s saving acts in Christ and the explanation of those acts in Christian theology. Considered subjectively, it refers to the Christian’s personal apprehension of Christ’s benefits sola fide (loc. 300).

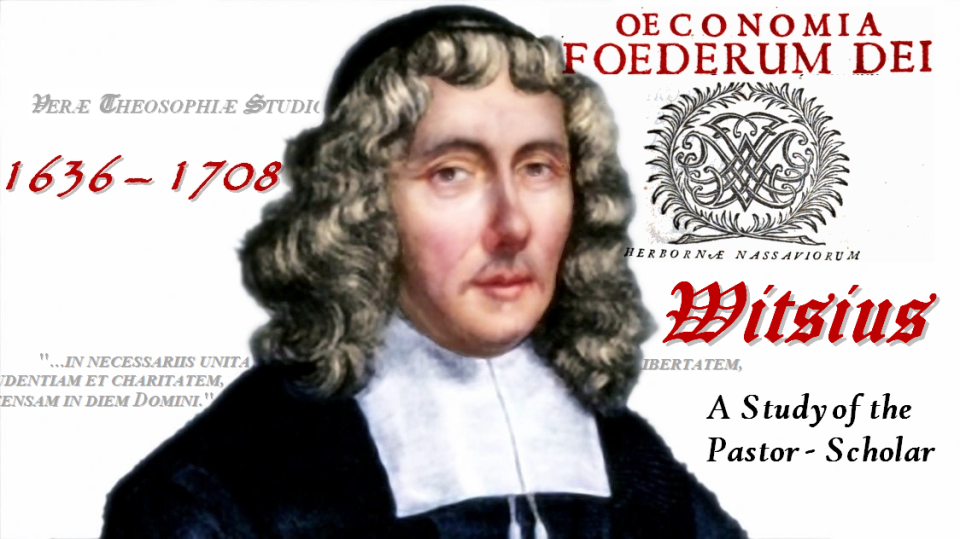

Before Olevianus begins his exposition of the Creed, he grounds the reader in the ideas of “kingdom” and “covenant.” Olevinaus notes that the “kingdom of Christ in this world is the administration of salvation by which Christ the King Himself outwardly, through the gospel and baptism, gathers to Himself and calls to salvation a people or visible church (in which many hypocrites are mixed)” (loc. 759). As is evident from his other work, this presupposes the distinction between the substance of the covenant and its administration. Regarding the substance of the covenant, he writes: “By His merit, Christ, the Priest and King of the church, ratified this covenant forever between God and us, and by his efficacy he daily administers it in us” (loc. 766).

In our understanding of this covenant, we see “certain fixed heads or articles, which are the foundations of this sacred reconciliation” (loc. 838). This move allows Olevianus to speak about the idea of the covenant in his exposition of the Creed. To be sure, the Creed does not actually mention a covenant per se, but Olevianus is on reasonably firm ground, given the above exposition. This is actually a very important conceptual move. By linking the Creed with the covenant, and by linking the covenant with Christ as mediator, Olevianus, representing the Reformed tradition on this point, is able to go beyond key Patristic gains. The Patristics rightly pointed us to the person of Christ in his divine and human natures. Olevianus receives this, but he points us to the person as mediator, not only between God and man, but also in his roles of prophet, priest, and king.

It is Olevianus’s claim (correct, I think) “that by the title ‘Christ,’ or ‘Anointed,’ the office of Mediator of the covenant is expressed, that is, the way and means by which the heavenly Father leads us by the hand of the Mediator (His merit and efficacy) to the salvation promised and sworn in the covenant (loc. 1640). Not only does Olevianus point us to the person of Christ, but he points us to the person of Christ as he is our Mediator of the covenant. It is by this way that we meet Christ and receive his benefits.

Regarding Christ’s virgin birth, Olevianus reminds us of a key distinction that is sometimes lost today: Christ’s human body and soul “were sanctified in this conception…by which all our corruption might be purged so as not to be imputed to us” (loc. 1777). This allows us to proclaim a real doctrine of original guilt and sin without having Christ be a sinner.

As regards the church, it is not surprising that Olevianus is strong where the modern church is weak. He reminds us of the marks of the church: “the truth of the prophetic and apostolic teaching is an indubitable mark of the church” (loc. 2937). (He mentions the word, prayers, and sacraments a few lines later.)

Conclusion

We are grateful to Reformation Heritage Books for making these classic Reformed texts accessible today. In many ways, and here I speak with fear and trembling, this is superior to Calvin as an introduction to the Reformed faith, if only by way of conciseness. Olevianus does not cover every topic (neither did Calvin), nor can he be expected to. The book is inexpensive and its content readily accessible for the average layman.